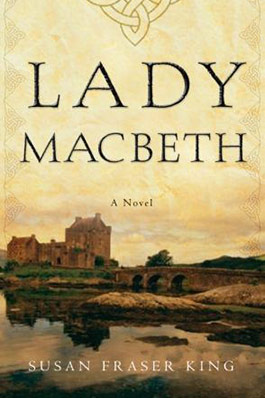

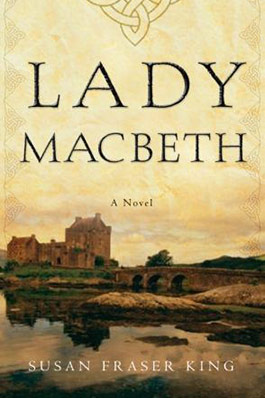

Lady Macbeth: A Novel

From towering crags to misted moors and formidable fortresses, Lady Macbeth transports readers to the heart of eleventh-century Scotland, painting a bold, vivid portrait of a woman much maligned by history.

Lady Gruadh—Rue—is the last female descendant of Scotland’s most royal line. Married to a powerful northern lord, she is widowed while still carrying his child and forced to marry her husband’s murderer: a rising warlord named Macbeth. As she encounters danger from Vikings, Saxons, and treacherous Scottish lords, Rue begins to respect the man she once despised. When she learns that Macbeth’s complex ambitions extend beyond the borders of the vast northern region, she realizes that only Macbeth can unite Scotland. But his wife’s royal blood is the key to his ultimate success.

Determined to protect her son and a proud legacy of warrior kings and strong women, Rue invokes the ancient wisdom and secret practices of her female ancestors as she strives to hold her own in a warrior society. Finally, side by side as the last Celtic king and queen of Scotland, she and Macbeth must face the gathering storm brought on by their combined destiny.

This is Lady Macbeth as you’ve never seen her.

"Captivating...An epic tale written in high-voltage prose...a ripping tale of love and ambition."

~ Publishers Weekly on Lady Macbeth

"A fascinating, layered story of Lady Macbeth: King's novel turns Shakespeare's play on its ear, setting history against fable as it brings a nuanced and fierce truth to the life of this much-maligned queen."

~ Professor Mary Bly, Fordham University (aka Eloisa James, NYT bestselling author)

Anno Domini 1058

Snowflakes dazzle against the evening sky and fall gentle around this stark tower. The false King of Scots expects us to trudge our ponies through that cold deep, so that I may tuck myself away in some Lowland monastery. Malcolm Canmore, he who murdered my husband and now calls himself king, would prefer I went even farther south into England, where they have priories just for women. There his allies would lock me away, as the Scots will not.

But my son is the crowned King of Scots now. I am under the protection of his name, and the strength of my own. Had I agreed to marry Malcolm Canmore despite all, I would be honored now. Weeks ago, at the turn of the new year, he sent a messenger with a length of green silk, gold-embroidered, and pots of spices and perfumes, with a request for my hand in marriage.

If power of that sort was what I craved, the gifts and request would have intrigued me. But I am a Celt and value honor more, and prefer Scottish wool to Oriental silk. Coarse by comparison, our weavings have the honest strength and handsomeness of this land.

I wrote an answer with the very hand Malcolm wanted, though my Gaelic script is worse than my Latin. Only a few words were needed for a refusal. I sent the note and most of the gifts back, and kept the silk. My handmaid, Finella, likes it.

As for convents, I will send another message to the usurper Malcolm: the dowager Queen Gruadh, lately wife to King Macbeth whom you have slain, chooses to remain in her fortress.

A dare of sorts, and we shall see what he will do.

The winds howl—it is no wonder February is called the wolf-month—and we sit, my companions and I, before the fire basket absorbing warmth and brightness. Dermot, my household bard, plays a melody on his harp. Shivering, I draw my cloak about my shoulders. Though I have lived scarce forty years and still burn with life, the chill riding the air this night is keen.

Servants draw curtains over shuttered windows that leak the cold, and then stoke the fire with peat and sweet applewood, branches saved from autumn. My little sons are gone to their peace—fair candles blown out too soon—and my husband is dead too. The endless evenings do need filling of late.

In shadows and firelight, two others sit with me listening to the harper’s music, while surly Finella moves in and out of the room like a wraith. Bethoc, seated nearest me, is my cousin and the healing woman in my household; the monk Drostan sits apart from us, his shoulders hunched as he reads the pages of a small book. Both of them ran with me as youngsters. Given my temperament, perhaps only Celtic loyalty has kept them with me since.

Bethoc is a true friend, though at times she judges me harshly, and I her. The monk is one of the Céli Dé, or Culdees, those who allow priests to marry and Sabbath to be celebrated on Saturdays, among other rebellions that delight me. In much else, Rome has nagged the Scottish Church to its knees.

Drostan, who has long known me, has a fine hand with a pen, and hopes to write a chronicle about me. This would be an encomium, a book of praise, for his queen. I told him it was a silly notion.

Sparks fly and small flames leap. Truthfully, I am considering it.

I am a granddaughter to a king and daughter to a prince, a wife twice over, a queen as well. I have fought with sword and bow, and struggled fierce to bear my babes into this world. I have loved deeply and hated deeply, too. I know embroidery and hawks and kingship, and more magic than I should admit. And I refuse to end my days in a convent. Now that is enough chronicle to suit me. Better to record the life of Mac bethad mac Finnlaech instead, the king who died near Lammas but six months past.

From what my advisors say, Malcolm Canmore—ceann mor in Gaelic, or big head, two words that suit him—will order his clerics to record Macbeth’s life. Within those pages, they will seek to ruin his deeds and his name. My husband cannot fight for his reputation now. But I am here, and I know what is true.

My mother, who crossed the threshold of life years ago, once peered into still water for a vision and said that one day the world would immortalize me without understanding me. That will come after my lifetime. I do not care to be remembered, whether it is clear or sullied. Besides, if my life is not done, why memorialize it. I might yet choose a new husband; I could have children again, for my womb still ripens. I refuse to cross the threshold of age.

Perhaps I will take up my sword again, summon an army and ride with my son to seek revenge, or weave a spell and undermine the usurper in some secret way. A few know my temperament and my wicked ways, my kindnesses, too: some do.

My memories are mine to keep. I fold my arms, satin and wool rustling, silver bracelets chiming. Bethoc looks up, Drostan too. They exchange glances. When I need it, I can call bitterness around me like mail armor, every thought a knot of steel, shielding the tenderness I have learned to hide as daughter, mother, wife, and queen among warriors.

Snowflakes drift through a window, and a serving girl draws the shutters tight by reaching with a long stick. We will go nowhere for days. But the music sweetens the silence, and we have stocks of imported wine and spices, plenty of smoked meats and fish, and barrels of grain in the storerooms of this stout fortress. We have two Roman priests willing to save our backward Celtic souls with proper prayers, and among our warriors are a few Norman knights who came north to stand with Macbeth, and remained as sword and shield.

We few in this room are a cluster of Celts gathered against a storm. The old Scotland fades into the new. I feel the threat blowing toward us like a great wind.

Some truths there are which must be said, and I wonder if I have that much courage in me.